Have you ever gazed at a painting and felt like you could step right into the scene?

That sense of depth and realism is often achieved through a powerful technique: linear perspective in art. For centuries, artists have used this mathematical system to turn a flat canvas into a three-dimensional world.

Understanding it isn’t just crucial for creators looking to master realistic representation; it also deepens the appreciation of any enthusiast.

In this blog, we will learn about the practical applications of linear perspective, unlocking its beauty and logic behind one of the art’s most enduring tools.

What Is Linear Perspective?

Linear perspective art is a geometric method used to create the powerful illusion of a three-dimensional world on a flat, two-dimensional surface.

The entire system revolves around the principle that parallel lines receding into the distance appear to converge at a single point, called the vanishing point, which is always located on the horizon line (eye-level).

These imaginary converging lines are known as orthogonal lines.

The linear perspective systematically mimics how objects appear smaller and closer together the further away they are from the viewer, tricking the brain into interpreting the flatness of the canvas as tangible, measurable space.

Linear perspective’s effectiveness in art relates to how the human eye perceives the world, taking advantage of the fact that distant objects appear smaller on the retina.

The Principles of Linear Perspective in Art

Mastering linear perspective art requires understanding its three primary forms, each dictating the number and placement of vanishing points to achieve a specific spatial effect.

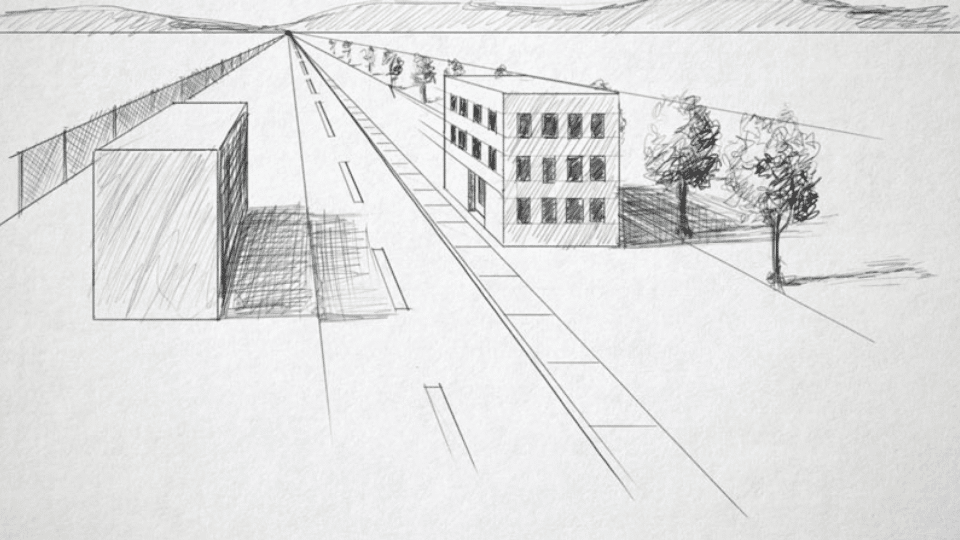

1. The One-Point Perspective

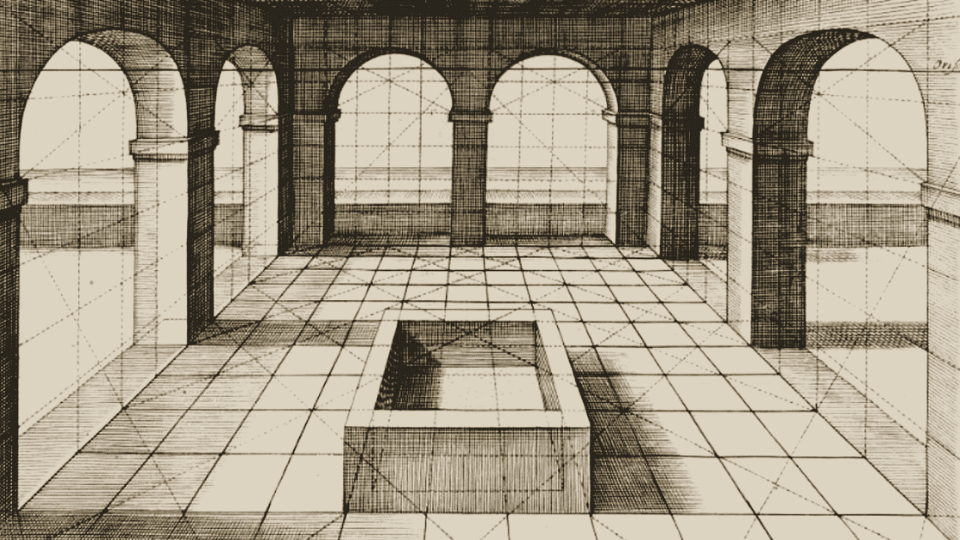

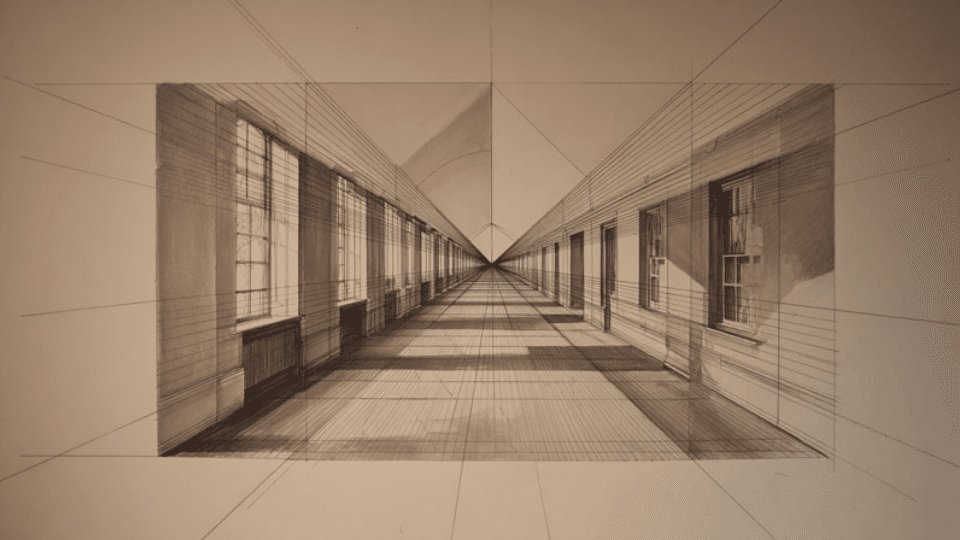

One-point perspective is the simplest form, characterized by having a single vanishing point directly on the horizon line. This point is where all orthogonal lines appear to converge.

It is best suited to scenes in which the viewer is looking straight ahead at a flat plane or wall, creating a sense of deep recession.

Famous examples include long interior spaces, such as hallways or train tracks leading away from the viewer, as well as the powerful symmetry in Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

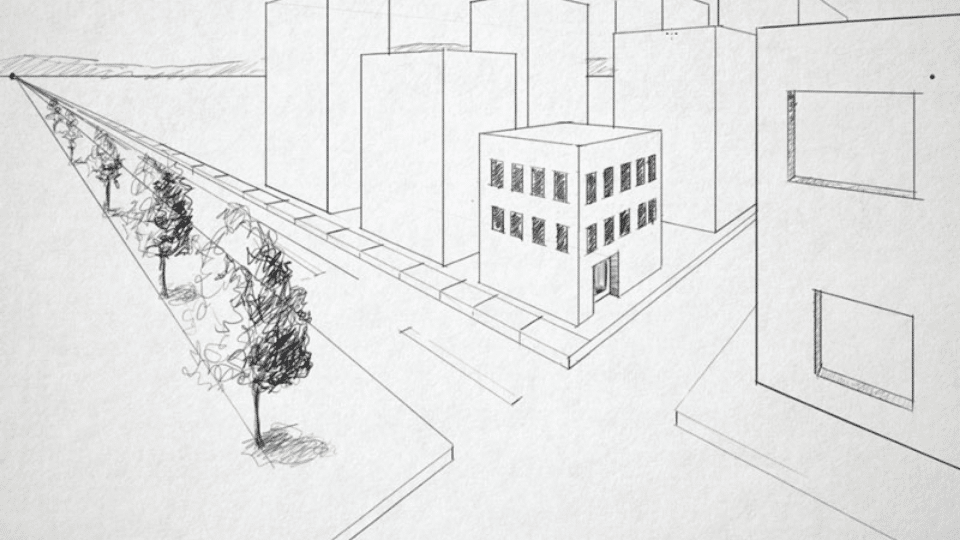

2. The Two-Point Perspective

Also known as angular perspective, two-point perspective uses two separate vanishing points on the horizon line.

Unlike one-point perspective, the subject is turned so that the viewer sees an edge or corner closest to them, rather than a flat face.

The two sets of parallel lines (representing the sides of an object, like a building) recede and converge toward their respective vanishing points.

This technique is commonly used for realistic architectural drawings of buildings seen from an angle and vast landscapes, providing a less rigid sense of space.

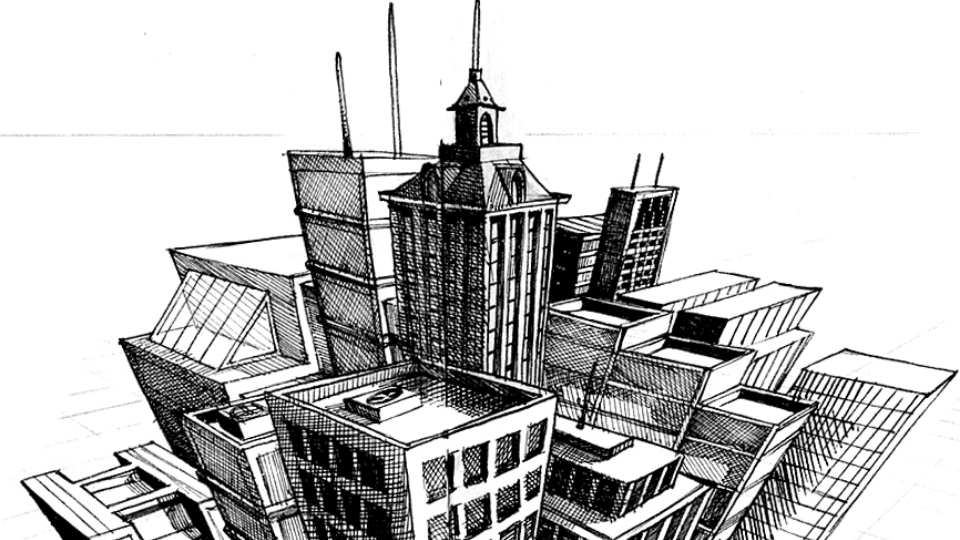

3. The Three-Point Perspective

Three-point perspective is the most advanced form, incorporating a third vanishing point that is either high above or far below the picture plane.

By adding the third point, the artist can simulate the dramatic distortion that occurs when a subject is viewed from a very high or low vantage point.

This technique is essential for creating the towering, monumental effect of skyscrapers or colossal structures.

The History of Linear Perspective in Art

The path of linear perspective art from a theoretical concept to a fundamental artistic tool spans centuries, marking a profound shift in how artists approached the depiction of reality.

1. Early Attempts at Depth Before the Renaissance

Before the 15th century, the creation of depth in painting was rudimentary and inconsistent.

- Hierarchical Scale: In medieval and early art, the size of figures often reflected their spiritual or social importance rather than their physical distance from the viewer. For example, a king or a saint would be drawn larger than an ordinary person, regardless of their position in the scene.

- Intuitive Depth: Artists sometimes attempted to create a sense of space through overlapping objects or intuitive perspective, where lines seem to converge but do not follow a precise, geometric system, resulting in visually distorted or shallow space.

2. The Renaissance Revolution

The 15th-century Italian Renaissance brought about a radical change, changing painting into a science.

- Brunelleschi’s Discovery: The Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi is credited with finding the mathematical principles of linear perspective around 1420.

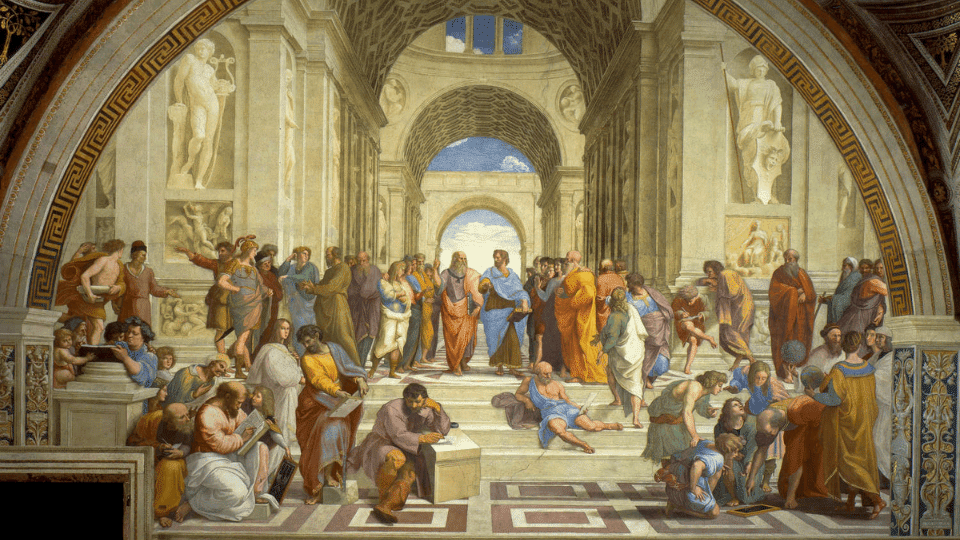

- Mastery and Refinement: Masaccio utilized it in his groundbreaking fresco, The Holy Trinity, while later masters like Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael perfected the technique, employing it to create the harmonious and deeply realistic compositions seen in works like The School of Athens.

3. The Spread and Evolution of Perspective

The impact of linear perspective art quickly spread beyond Italy, changing the course of art and design.

- Global Influence: The technique rapidly diffused across Europe, influencing the works of Northern Renaissance artists like Albrecht Dürer, who wrote treatises on the subject, making it an essential part of an artist’s training.

- Modern Art Shift: While a core skill, 20th-century movements like Cubism and abstract art intentionally fragmented or abandoned linear perspective art, proving its enduring power by making its rejection a powerful artistic statement.

How do Artists Use Linear Perspective Today?

The foundational rules of linear perspective remain crucial not only for traditional art but also for modern and digital visual fields, serving both as a tool for realism and a convention to intentionally subvert.

Realism and Architectural Drawing

The principles of linear perspective in art are essential across various professional disciplines that demand spatial accuracy.

- Digital Illustration and Concept Art: Contemporary illustrators, especially those working in video game development, film, and comics, rely heavily on what is linear perspective to construct believable, immersive environments and backdrops.

- Architectural Visualization (ArchViz): Architects, draftsmen, and 3D modelers use one-, two-, and three-point perspectives every day. These techniques are vital for creating realistic, understandable blueprints, renderings, and walk-throughs of buildings, ensuring structural and spatial integrity long before construction begins.

Creative Distortion and Abstract Use

Beyond mere realism, many contemporary artists manipulate linear perspective art for powerful expressive and conceptual effects.

- Surrealism: Artists like Salvador Dalí often employed meticulous linear perspective art to draw the viewer into a hyper-realistic space, only to populate it with illogical or dreamlike objects, intentionally unsettling the viewer by contrasting a rational framework with irrational content.

- Breaking the Rules: Other artists intentionally use multiple vanishing points within a single plane or shift the horizon line dramatically to create a sense of disorientation, movement, or psychological tension.

Practical Ways to Learn Linear Perspective

Here are actionable tips to help you master linear perspective in art and sharpen your spatial awareness:

- Establish the Horizon Line First: Always begin by defining the horizon line (which represents your eye level). This is the absolute foundation; all vanishing points must rest on this line.

- Use Light Pencil Guidelines: For every drawing, lightly sketch your orthogonal lines connecting the corners of your objects to the vanishing point(s). These guidelines are your “depth map” and are erased once the final forms are drawn.

- Break Down Complex Objects: When drawing a complex object, such as a building or a car, first enclose it in a simple transparent box using one- or two-point perspective.

- Practice with Interiors: Draw simple room interiors using one-point perspective. Place your vanishing point directly opposite the viewer to practice drawing parallel lines for the walls, ceiling, and floor that converge correctly.

- Draw from Observation: Go outside and practice sketching a street corner or a hallway, actively finding the horizon line and vanishing points in real life.

The Bottom Line

For the artist, mastering this geometric language unlocks the ability to create believable, immersive space; for the enthusiast, recognizing the vanishing point and horizon line deepens the appreciation of a masterpiece’s construction.

Now, we encourage you to look at the world and art around you in the receding lines of a street or the carefully mapped walls of a fresco and observe its powerful logic in action.

Practice these techniques, and you’ll gain a profound new level of skill and spatial understanding.